Last year, DC Comics--one of the two biggest comics publishers in the world--began releasing titles under it’s DC Ink imprint. This specialized line of graphic novels feature one-shot tales about some of DC’s biggest heroes and antiheroes, like Catwoman and Harley Quinn, with a special twist: they’re aimed at younger readers.

DC is no stranger to comics for young readers. Their Zoom imprint aims for a middle school demographic, favoring manga-styled versions of familiar heroes. DC also has a history of television shows for young people, including Super Hero Girls, which follows teen versions of heroes like Wonder Woman and Batgirl.

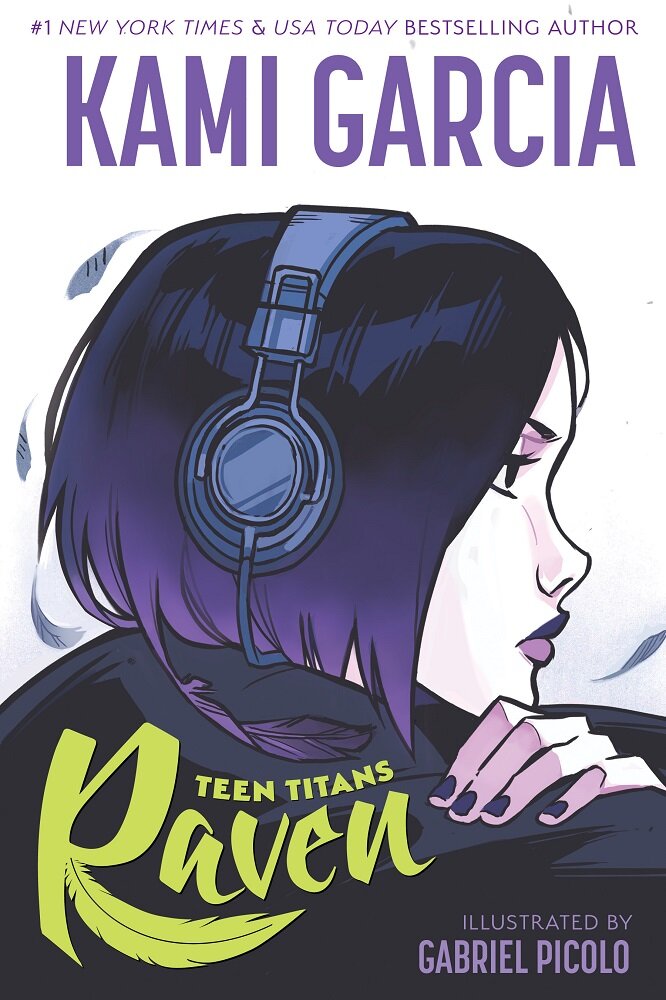

But DC Ink seems to be doing something different than other properties aimed at young people. Instead of throwing the reader into an already established plot line, or rehashing a tired origin story, the Ink books reframe beloved heroes by having them face issues actual teenagers confront in their daily lives. In Mera: Tidebreaker, a 15-year-old Mera (one of Aquaman’s associated heroes) must figure out what it means to be a princess of the ocean. A 15-year-old Harley Quinn has to figure out how to navigate gentrification in Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass, while a young Raven has to discover who she truly is through wrestling with issues of identity in Teen Titans: Raven.

While all of these stories have elements of heroism, they aren’t always related to fighting crime, partially because the characters are limited by a system that denies them agency due to their youth. Because they can’t go out and fight crime as they will when they’re adults, these teen would-be heroes have to deal with more mundane—but no less significant—issues. If young adult literature, which the Ink line is attempting to tap into, illustrates the process of young people finding their place in society, then these graphic novels are showing teen and adult readers alike that the landscape of youth has changed. I’m not sure that gentrification would have been on my mind when I was 15, but I’m sure that young people today are thinking about it, just as adults are thinking about it.

Often, when big corporations like DC attempt to make a young adult line, things go wrong. The tone comes off as patronizing or the plots fall flat. Maybe the art is bad on top of everything else. However, the Ink imprint avoids this by featuring different authors and artists for each volume, letting each creative team make the character “their own,” as Kami Garcia notes in her introduction to Raven. Familiar YA voices like Meg Cabot and Mariko Tamaki are among the authors featured so far, and artists like the viral sensation Gabriel Picolo help in refreshing old character designs and imagining what these heroes might have looked like as teens.

Some of Picolo’s Teen Titans art, which imagines them as high schoolers doing normal teenager things. Image from Twitter, @_gabrielpicolo

Young people deserve to have stories that reflect their concerns and obstacles regarding their identities and the world around them. The world is a scary place right now, much scarier than even fifteen or so years ago when I was a young adult myself. Literature, and maybe especially comic books, are supposed to help comment on and examine issues that seem confusing and dark. In the 1970s and 80s, comics saw a rise in story arcs about drug abuse because, at that cultural moment, the general public felt anxious about drugs they didn’t know about. Now, we need different sorts of stories for young people, who receive education about drugs and sex (though that education can always be better) from an early age. Now, we unfortunately need stories about bullying and identity politics, about mass shootings and war, about climate change, about class. The Ink line is making steps to tell some of those stories, and tell them in an interesting, fresh way.

You can find out more about the Ink line of comics here.

Bb Catwoman is very cute!