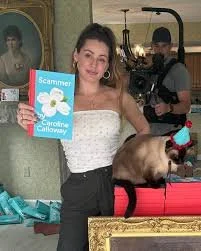

In 2020, I preordered Caroline Calloway’s debut book, Scammer.

For anyone familiar with Calloway’s tendency to shirk responsibility for her blunders (in a cute, whimsical way, of course), the fact that I actually received Scammer in 2023 after months of messaging the author online should come as no surprise.

Journalists have long detailed Calloway’s life in various articles, and of course author Natalie Beach has given her side of the messy story in an infamous article for The Cut. Here’s the brief version: Calloway rose to fame after buying Instagram followers in a time when it wasn’t frowned upon to do so, then she gained more followers by writing long captions about her life at Cambridge. She sold a book based on her life at Cambridge (and her Instagram’s aesthetic), but after writing the proposal with her friend Natalie Beach (and receiving a hefty advance), Calloway decided she didn’t really want to write the book at all – or at least not in the way she’d pitched her publisher.

This is when I first heard of Calloway, when she was desperately hosting DIY “workshops” at various places in New York, overordering mason jars, and generally trying to make money any way she can. She sold “Snake Oil,” a skin care serum she cooked up in her own New York apartment, created an OnlyFans account where she cosplayed as sexy literary heroines, and created Matisse-inspired art that she sold for hundreds of dollars to strangers online. While I had no conception of Calloway’s previous life as an Instagram influencer, I quickly became acquainted with her “scams,” and felt she was kind of a genius for it. After all, people were buying the art made out of scrapbook paper, snapping up the Snake Oil, and paying fees to see Caroline topless on OnlyFans. Honestly? Good for her.

So when Calloway announced she’d be writing a book based on her life, from her point of view, I knew I had to order it, even if there was a high chance I’d never actually receive it. Then, in 2023, Calloway began sending out copies of Scammer to journalists. I updated my address on my order (I’d moved twice since ordering), and eagerly awaited my copy. And waited. And waited. Eventually, I started messaging Calloway whenever she promised others copies of the book. With a small amount of pride, I say I annoyed her into sending my copy along. It’s not an untrue description.

The packaging was cute though.

But I want to talk about the book itself. As a physical object, it’s gorgeous. With hand-glued end papers, a customized Ex Libris sticker featuring Calloway’s cat, and a striking, Tiffany-blue cover, Scammer does feel like a work of art – or at least an approximation of it. Still, there are odd details that mark it as a homemade project (in a charming way). When one of the end papers was glued in crookedly, hanging off the bottom of the hardback and leaving a gap at the top, it’s clear someone painted in the gap with a paint pen. That sort of attention, even if it’s a homemade solution, is endearing.

Aesthetics aside, what about the actual contents of the book? I’m not quite sure how to approach Calloway’s first foray into longform prose, and I really don’t think she was either. The memoir intentionally tries to provoke readers, beginning with an extensive description of how Calloway has never experienced an orgasm, despite being an incredibly sexual being, as she reminds readers repeatedly. Part of Calloway’s writing schtick is breaking the fourth wall so-to-speak, and telling the reader directly how she’s crafting the contents of her work. She bluntly explains that she wanted to “slap [readers] like a dead fish to the wet face. There was too much pressure on how I’d open my first book up to do anything but gobsmack. Or else I’d still be out there, treading water in a windless sea of not just writer’s block, but paralysis, salt-water warm and amniotic as a bath, as the Atlantic is in Florida.” That said, Calloway continues to drop surprising “gobsmack” throughout the book, sharing secrets that come across as cruel rather than humanizing.

Calloway’s relationship with Natalie Beach lies at the heart of the memoir, and it details some of the harshest writing Calloway has to offer in Scammer. In her attempt to lay her feelings bare before the reader, Calloway shows some mean-girl tendencies. She frequently talks about Beach’s appearance, once comparing her to a frat boy. Meanwhile, Calloway highlights how feminine she is, how delicate her aesthetic. Where Natalie can’t find even one romantic partner, Caroline has her pick of Cambridge’s elite. Though Natalie has all the right connections (like an aunt who works for O Magazine), Caroline has to work hard for her success. Despite reading about Calloway’s chaotic childhood, it’s difficult to think of her as anything but privileged, and in framing Natalie as an insidious, two-faced friend, Calloway only muddies her own character.

TW: Undetailed mention of SA to follow.

Caroline Calloway via Instagram

Most egregiously, Calloway recalls the night that Beach called her to share the details of her sexual assault, crying as she explained every step in the process. Calloway recalls feeling turned on at hearing Beach’s trauma. Instead of feeling sympathy or empathy, she felt wet.

I know that in Caroline Calloway’s world this is a bigger comment on how she flirts with bisexuality, how she finds women attractive and mysterious. But the whole scene is gross, and it feels exploitative. It’s clear that Beach’s article for The Cut wounded Calloway, but it’s unfair to write so lewdly about her personal trauma as some sort of revenge.

On the whole, Scammer shows a side of Calloway that doesn’t always get depicted on Instagram. She’s twee and flighty, sure – she could walk out of a Selkie ad at any minute – but she’s also manipulative and deceitful in her own way. Every move – to Cambridge, to New York, to Florida – feels meticulously calculated. Yes, the nuanced relationship Calloway has with addiction and recovery is interesting, and a difficult situation, but it doesn’t excuse her behavior in this book.