2019 is the year fraud documentaries assume the mantle formerly held by murder documentaries in 2017-2018. Fraud is having a real pop culture moment, and I, for one, am super on board. In January, Netflix and Hulu treated us to Fyre and Fyre Fraud, respectively, and people ate these documentaries up. (“People” includes Mary and me. Read our Fyre Festival docs blog to see why we were so enthralled.)

This month, HBO blessed us with The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley, a documentary about “innovator” and business founder Elizabeth Holmes and her ill-fated healthcare startup, Theranos. While this fraud doc has fewer private jets, zero supermodels, and absolutely no Ja Rule, I might be even more obsessed with Holmes and Theranos than I was with Fyre Festival. Let’s talk about this schadenfreude smorgasbord. Some spoilers to follow.

Part of why we’re all loving these fraud stories is that it’s strangely fun to watch things go so, so wrong. While Fyre Festival had a really quick rise and fall, Thernos’s astronomical climb and subsequent crash/burn took a lot longer and cost people a lot more money. Instead of millennial Instagram influencers getting tricked, venture capitalists, CEOs, and state department officials were duped. By a 19-year-old Stanford dropout.

While in college, Holmes had an idea that could revolutionize healthcare and medical testing: instead of getting vials upon vials of blood drawn for common blood tests, Holmes’s “invention” would allow 200 different blood tests to be run on a fingerprick’s worth of capillary blood (though this number would change several times along the way). In theory, it’s a great idea. The problem: Holmes and Theranos never had the technology to actually do this. It’s like thinking, “Wouldn’t it be cool if I could fly to work?” but telling everyone you invented a flying car and asking for millions of dollars for it.

Same logic.

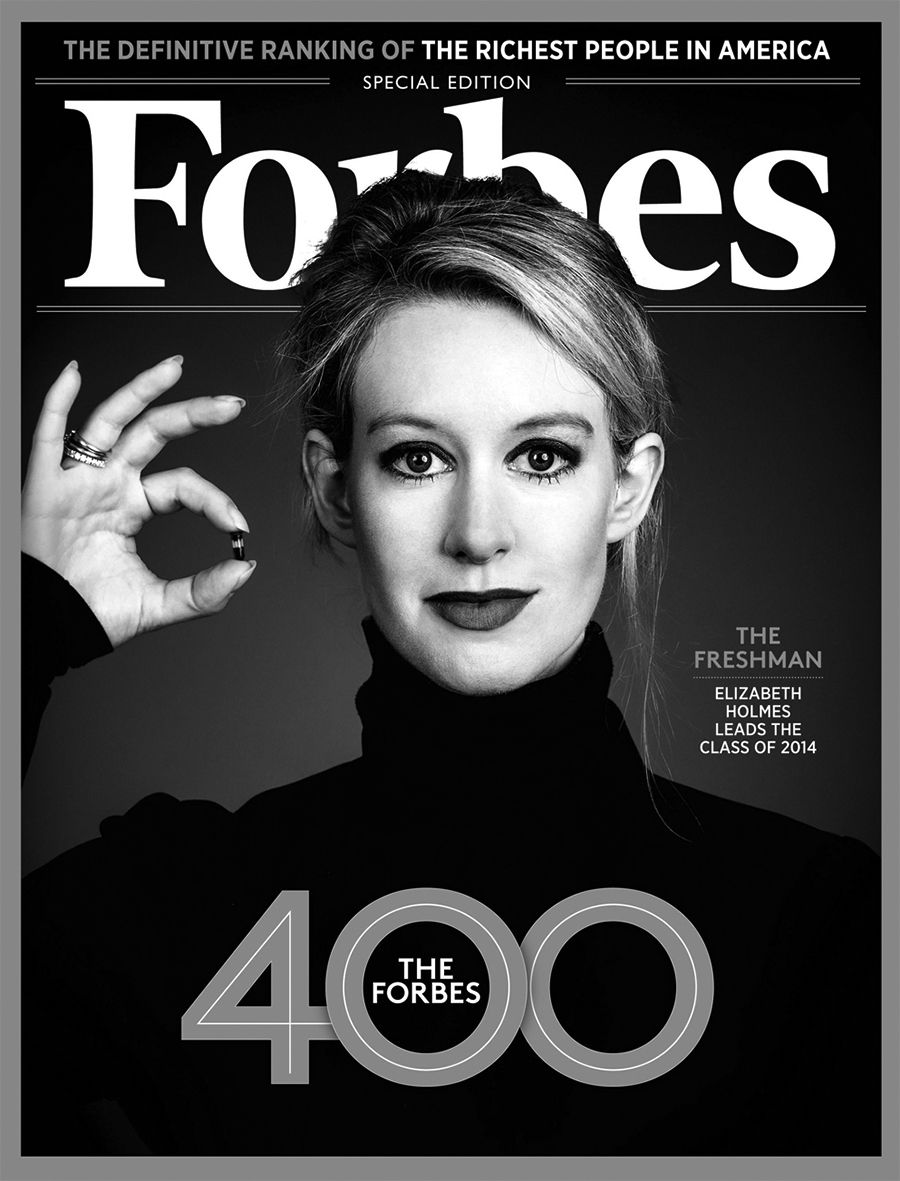

What Holmes had was an idea, not an invention. And yet somehow, she fooled a lot of people into thinking she was the next great American inventor. In the documentary, Holmes quotes Thomas Edison, someone she revered as an inventor, but the documentary warns that Edison’s greatest invention was...himself. For Holmes, this is also true. Some blonde girl named Elizabeth Holmes created Elizabeth Holmes™, founder and CEO. And let me tell you, this character is a doozy.

First, she idolized Steve Jobs, to the point that she copied his black-turtlenecks-only wardrobe in an effort to cut down on the number of decisions she had to make in a day. In The Inventor, we hear her say she’s been in black turtlenecks since she was seven years old. I call bullshit. She’s lucky if there happens to be one picture of her wearing something similar as a child. In Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (because you know I had to get this book immediately), John Carreyrou writes that the wardrobe decision was actually a move Holmes made based on a suggestion from a colleague when Elizabeth was an adult. According to this person, in the early days of the company, Holmes wore frumpy, ill-fitting grey pantsuits and did not look at all like a leader. So she changed the way she looked. So the look became: black turtlenecks and black slacks, messy black eyeliner, hair in a semi-messy bun. I suspect the “messy” makeup and hair were purposely so, in an effort to look like “Who has time for makeup when you’re running a totally real and legit company?!”

Next, there’s THE VOICE. Holmes put on a deep baritone to...communicate gravitas? To sound more masculine? To sound authoritative? I do not know why, but y’all, it is a lot. And a deep voice on a woman is nothing to make fun of or even comment on if it is real. But this one is not. Sources in the book told Carreyrou that when Elizabeth would drink, she’d often forget her pretend voice and slip into her “regular” voice, which was described as “an octave higher.” The Inventor addresses this as well, and there are tons of videos out there dedicated to showcasing her “real” voice .

Wearing black turtlenecks and speaking in a voice that can only be described as a child trying to sound like an adult, Holmes convinced some big players – including Henry Kissinger and Gen. James Mattis – that Theranos would change the world. And yes, the technology she pretends to have does sound like a good idea, but Theranos never proved to anyone that any of their stuff actually worked. In fact, the opposite seemed to be true. But people were sold on Elizabeth.

Don’t look directly into her eyes.

She’s fascinating to me much like Billy McFarland was in the Fyre Festival documentaries. Even staring at all the evidence of impending implosion, people still bought into what Billy and Elizabeth were selling. Carreyrou reveals in the book, for example, that the board and other leaders tried to remove Holmes as CEO and put her in an another role early in the company’s growth period. After several hours of meeting, Elizabeth talked them out of it and remained in charge. I imagine she made her voice even deeper for this challenge.

Each time a scientist or Theranos employee brought concerns to Elizabeth or Sunny (we’ll get to him in a sec), they reacted with anger, defensiveness, and more often than not, an unceremonious termination of employment. Sunny, Elizabeth’s second-in-command, fired a lot of people. His management style sounds beyond problematic in Carreyrou’s book, but what’s even more problematic is that Sunny and Elizabeth were in a romantic relationship. And living together. And didn’t disclose it to the board or anyone, even though Theranos was footing the rent for their big-ass mansion. Uhhhh, what?! Ok, so clearly we’ve got ethical problems on the personal front, but what about the medical front?

The Inventor gives glimpses of the problems with Theranos’s blood testing technology, at one point showing a computer animation of the problems with blood basically being sprayed and spilled all over the inside of the machine. Bad Blood dives deeper into testing issues with stories of real patients who got false abnormal results that could have had disastrous effects if they’d been treated for their “conditions” before their doctors ordered a re-test at a non-Theranos facility. Up until real patients are involved, this is just a story of tricking investors. At this point in the book, it hit me how seriously dangerous all this was. Elizabeth Holmes is lucky no one died as a result of being treated for a condition they didn’t have.

On top of these lies (as if we need more), Elizabeth and Sunny straight up tested collected blood samples on non-Theranos machines and told people that they were using the Theranos equipment. Carreyrou details the charade of them collecting VIP visitors’ fingerprick samples and putting them into the Theranos machine, then taking them out when the VIPs left the room and testing the samples on non-Theranos machines, then giving those people their results as if they’d run the tests using their own technology. I kid you not.

Perhaps the most alarming part of Bad Blood is Carreyrou’s telling of how his original Wall Street Journal article exposing Theranos came to be -- and everything Theranos and its attorneys did to try to stop it. Theranos’s lawyers threatened more than one Carreyrou source with expensive litigation, and they said they’d sue the paper itself if the story ran. Since the attorneys were representing a highly unethical company, it should be no surprise they also used unethical tactics to save face when they realized how damning the article would be. I won’t spoil this because it’s a great part of the book.

After the article ran, things got even worse. This is where it becomes clear, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that Elizabeth, Sunny and the Theranos attorneys 100% knowingly lied to everyone. Even faced with direct, clear evidence of their fraud, Elizabeth went on to publicly recite falsehood after falsehood. At no point did anyone stop this crazy train, and by then it was too late, so everyone rode it off a cliff.

Dr. Gardner, Elizabeth’s former teacher and actual medical professional, who tried to tell her this whole thing was never going to work.

I think part of what makes this story so fascinating is that Elizabeth Holmes would have been such a tremendously positive figure for women and young girls if her story and her company were real. For a time, the person she invented was exactly that. Silicon Valley, tech startups, and the STEM field in general are largely dominated by men. A young, hungry, dedicated woman starting her own company that was at one time valued at $9 billion is something that girls in STEM probably needed to see. It’s what made Holmes’s story so easy to root for, and it’s what makes it twice as disappointing that it was all a fraud.

But in the meantime, I present to you Erika Cheung, who is actually badass scientist and had the guts to blow the whistle on Holmes and Theranos when she was just a 22-year-old junior Theranos employee. She didn’t found a company (yet), but she did face some serious intimidation and threats for doing the right thing, and she did it anyway. Erika > Elizabeth.

Erika Cheung

Photo by David Buchan

If you’re as obsessed with this crazy story as I am, definitely watch The Inventor. It’s about two hours long and includes interviews with whistleblowers and former Theranos employees, as well as plenty of footage of Elizabeth and Sunny through the years. I recommend Carreyrou’s book even more highly. Bad Blood offers a more in-depth investigation into Elizabeth and the rise and fall of Theranos. You get a fuller sense of her as a person and what makes her tick, and you get more dirt on the company’s shady activities. The audiobook is great if you’d prefer to listen.

What do you think is the wildest part of the Elizabeth Holmes story? Tell me so we can discuss the deets!