Kelli: Hello and welcome back to Queer Girl Book Club! I’m your host, Kelli. Just kidding, this is a blog post.

This month we’re talking about You Exist Too Much, the debut novel by Zaina Arafat. The story follows a Palestinian-American young woman as she navigates her twenties. Our narrator is never named, which I only noticed about halfway through the book. I thought to myself, ‘what’s her name again?’ and then flipped through for a while before I realized she didn’t have one. I was surprised, I guess because I felt like I knew her so well already. So I guess a good way to start this discussion is to ask: how did you feel about the narrator?

(Spoilers to follow)

Emily: I agree. She felt like a real person, which is I think what a lot of people mean when they say something reads like a memoir. This felt memoir-like because the character felt real and it was told from the first person and since she didn’t have a name, I guess it does make it seem a bit closer to the author.

I always wonder why authors choose not to give narrators a name. Like what do they feel like that does for the story? What is the intent with that, do you think?

Kelli: I wonder if it had to do with wanting to emphasize the sense that this character exists in so many in-between and uncertain spaces with regards to her identity. She feels simultaneously like “too much” and not quite enough. She also defines herself based on her relationships with other people, whether it’s her mother or her romantic entanglements, and she seems like she’s constantly searching for some sense of self. I felt like it fit here, the namelessness, but there have definitely been times I’ve questioned it in other novels, so maybe I’m just giving Arafat the benefit of the doubt because I liked this book, lol.

There are so many different topics to cover here, but since this is Queer Girl Book Club, let’s talk about the queerness. A few of the books we’ve read for this series have ended up being sort of tangentially queer, but queerness is a real focus here, and that made me happy. The narrator never explicitly defines her sexuality, but at one point someone refers to her as “bisexual” and she doesn’t disagree with them. Which is good, because I’ve been referring to this novel as “the bisexual book.”

Emily: Right, and I think whether or not she identifies as bisexual or pansexual or whatever else, at the end of the day, this books shows he having serious relationships with both men and women, so it’s definitely speaking to bisexuality, whether it’s named that or not.

Kelli: Wrapped up in the queerness, though, is the narrator’s sex and love addiction, which she struggles with throughout the book. I found this fascinating because, as we know, one of the most common stereotypes of bisexual people is that we are never satisfied. This is a tricky thing to navigate. How do you think the novel works with and against this stereotype?

Emily: Ooh, that’s a tough question. Well, for one, I appreciate that the “cheating” the narrator does is more emotional cheating than physical cheating, which of course speaks to love addiction rather than sex addiction. But I think one of the stereotypes of bisexuals is that they’re really just “slutty.” And she’s not really going out having sex with everyone. Flirting with everyone? Sure. Daydreaming about everyone. Okay, yeah. But like, maybe she’s just a Libra.

The other thing too is something that’s so obvious I feel kind of dumb saying it. But it’s not like she’s having relationships with men and women at the same time. It seems like she’s usually crushing on women when she’s in a relationship with a woman. So it’s not like she’s sitting there thinking, “I can’t get everything I need from this person because she’s a woman and not a man and I need both.” Really, she doesn’t seem to think about gender much at all when she’s finding her love interest. It’s more about their personality and what kind of emotional connection she has with them (which is why I was thinking she might identify as pansexual, but I can’t label people so I am not doing that). The only time a partner’s sex/gender comes up is when she has to justify herself to her mother.

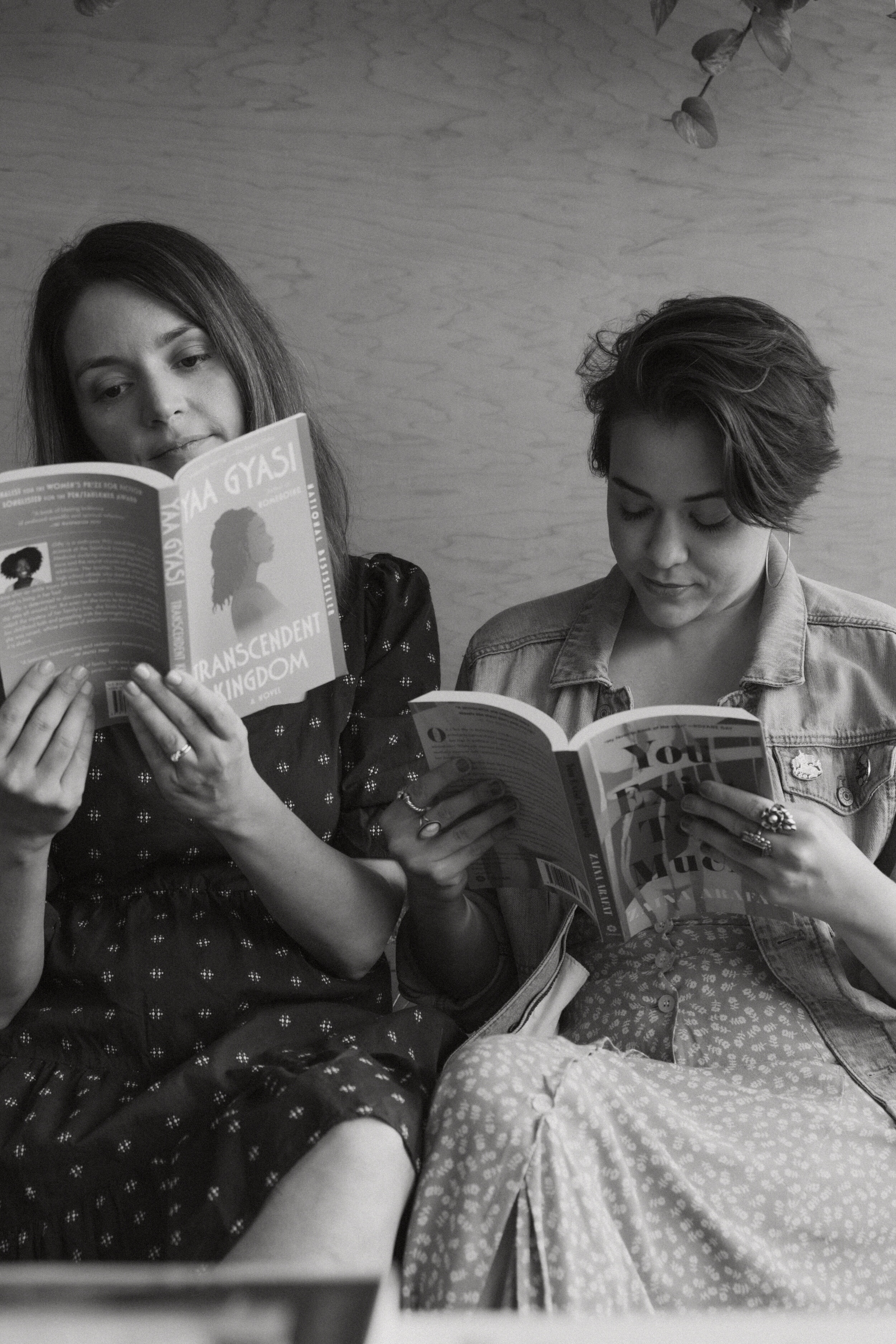

live footage of kelli, known bisexual, pretending to read this book. (photo by Katelyn Elaine Photography)

But what do you think? I feel like you probably have a better answer for this question than I do.

Kelli: That is a really good point about her not seeking out people of the opposite gender from whoever she happens to be in a relationship with, and you’re right that it refutes the stereotype that bisexual people will never be satisfied with “one or the other” (which obviously doesn’t even take nonbinary people into account but I digress). I thought Arafat did a good job of showing us that this really is an addiction and not just a quirky personality trait, establishing the narrator’s patterns so that the reader can recognize what’s happening each time she becomes involved with someone new. She says something about becoming fixated on the dip in a person’s collarbone as the first sign of a romantic obsession, and I thought that was such a specific and interesting detail. I can see how this type of addiction can be linked to obsessive compulsive disorder, how the obsession spirals outwards and the compulsions to act on it feed the cycle.

We also have to talk about the narrator’s relationship with her mother, Laila. It is implied that Laila has Borderline Personality Disorder, though it’s also apparent that it’s not something she herself has ever acknowledged or tried to deal with.

Emily: I really identified with this part of the story because I also have a difficult relationship with my mother and my mother also struggles with mental health issues. Heck, I do too, so no shade to mental health issues. Thankfully, my mother has never threatened to disown me because of my sexuality. However, the way her mother constantly criticizes her, I really felt that on a deep, personal level. And obviously the stuff with her mother is SO important because that’s where the title comes from. “You exist too much” is something her mother says to her.

I know your relationship with your mother is very different from mine (lol understatement). How did you feel about this part of the story?

Kelli: My relationship with my mom is pretty different than this, yes, but it still rang really true to life as I read it, probably because you and I have talked a lot about your situation — and I was definitely thinking about you here, lol. I felt like this was maybe the strongest thing about the novel, or perhaps the most emotionally resonant, especially in the way the narrator is so desperate for things to work out with her mom. She knows that her mother is judgmental and critical and withholding, but it doesn’t stop her from repeatedly trying to come out to her mom, each time hoping that this time will be different and she’ll finally be accepted for who she is. This need for approval the narrator is holding onto is this primal, animal instinct that I can definitely relate to, because any time I’ve been in a fight with my mom I’ve ended up crying and apologizing and begging her to forgive me because I just want things to be right with her, even if she’s the one in the wrong. It’s so hard to operate from a place of objectivity when it comes to parents — especially mothers, in my experience anyway. We constantly feel the need to prove ourselves worthy of their love.

Emily: Yes, and I think the other thing that's so hard about arguing with parents (maybe especially moms) is you spend so much of your life thinking your parents are right and whatever they tell you has to be correct because they’re your point of reference for the world. They’re the ones teaching you how the world works and the difference between right and wrong. So when your mom tells you you’re wrong, it’s really easy to be like, “Well, fuck, she must be right because she knows the difference from right and wrong and I’m the kid.” Like even being in my 30s, my brain still thinks that way. So yeah, you do want to just make things right even if you know they’re wrong. And it’s really, really hard when you get older and this is complicated by the fact that you’re realizing your parents have mental health issues that skew their view of the world. And, like, maybe the way they see the world isn’t actually how it is. Anyway, I’m rambling. All of this is to say I really, really GOT this.

Kelli: Arafat jumps around a lot with the timeline here. Part of me liked the chaotic nature of it, and I always was able to hold onto the thread of the present moment, but some of the events that took place prior to the beginning of the novel were tough to keep track of. I know you had some issues with this, so would you like to elaborate? (Cue music for Emily’s Writing Corner.)

Emily: I do need a theme song, huh? Well I know while I was reading, I texted you a few times to tell you that I felt like the timing of everything was difficult to follow. Every story has a clock, and while things might not be told in chronological order, we as readers are able to follow along because in our brains we can pieces together where this story fits in the story clock in general.

Where I ran into problems with this was in a lot of the flashback moments. A lot of times, we would be in a present moment, and then Arafat would make some more generalized comment about how the character “always” does something or “often” does something. The problem with framing something as an action that happens often is that when you then go one to explain a story in detail, the reader is left wondering, “Wait, this isn’t an always situation. You’re now talking about a specific time one thing happened. But when did this thing happen? Is this happening now or is it happening in the past?” I would give you a specific example, but full disclosure it has been three-ish weeks since I read this, so I can’t remember a specific example. I think when she’s talking to about the emails she sends to her professor, we get into this problem, but I can’t remember specifics. I just remember that being the first time I noticed it.

Kelli: That is fair. I did notice that too, like an observation in a present moment would lead her into telling a story about the past that would stretch out to the point where it made it confusing when we would hop back into the present where we’d left off. There were other points where a full chapter would function as a flashback, and those were a little easier to follow, but it was the smaller flashbacks within present moments that were sometimes unclear.

What did you think of the way the novel wrapped up?

Emily: I like the idea of the narrator being in a happy relationship, and honestly I was glad it was with a woman. We haven’t talked about the one serious relationship we see between her and a man, but that man was garbage. Complete. Garbage. I think though that the possibility is left open that she’ll fuck up again. That’s always a possibility with addicts though. It’s nice in this instance to end on a note of optimism. What did you think? And if you also want to chime in on how shitty the dudes were in this book, feel free to do so. EL OH EL.

Kelli: Oh my god. The main relationship she has with a man is SO UPSETTING. At first it seems exciting and romantic, but then it devolves into absolute chaos. What I appreciated about it was that it came right after she got out of rehab, so it was her first real test of her recovery, and we see her reckoning with that, falling back into old patterns but also recognizing them as they happen, which is really the first step to getting better, as we all know. She can feel herself falling into the same old beats, becoming obsessive and devoting herself to this person too quickly, but the difference here is that he seems to be doing the same thing. There is a real power shift with this relationship, because up until this point in the story we’ve seen her treat other people the way he’s treating her — cheating, whether emotionally or physically, calling hundreds of times when ignored, performing the compulsive behaviors we’ve seen her engage in throughout the book. Whether or not he is having a parallel experience of addiction or is simply a trash bag is not really the point (I’m pretty sure he’s just trash tho) — the point is that she is finally experiencing what her behavior is like for the person on the other side of the equation, and I think that ultimately it’s an experience that moves her recovery forward.

Emily: That’s a good point, but I still hate him. Anyway. Should we rate this bad boy?

Kelli: Yes, I actually gave this five stars! If we were doing half stars I think it’d be more of a 4.5 for me, but I thought I’d push it up because a) I really enjoyed the experience of reading it and b) it was doing a lot and almost all of it was working for me. How about you?

Emily: I gave it four stars. I enjoyed it and it was a fast read for me, but for the time/pacing issues mentioned earlier, I had to cut a star because it was bad enough that it took me out of the story.

Kelli: What’s up next for QGBC?

Emily: Next up, we’re reading Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke by Eric LaRocca, which I’m so excited about because I’ve heard this book is bizarre and really messed up. Apparently it also asks the question, “What have you done today to deserve your eyes?” Which… that’s all I need to know. Let’s do this.