Earlier this month, Mariko Tamaki and Rosemary Valero-O’Connell released their graphic novel Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me with First Second. Mariko Tamaki might sound familiar; she’s written graphic novels that have helped shape the landscape of young adult comics in general, like This One Summer and Skim (both illustrated by Jillian Tamaki).

Emily and I wrote about This One Summer--we both enjoyed it, and I felt particularly attracted to Jillian Tamaki’s art style. Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me has a different tone than This One Summer, though, and follows a different sort of story. Instead of following children on the verge of figuring out their sexuality through puberty, Laura Dean depicts teenagers who have already been in relationships and feel more secure in their identity (though we know teenagers are rarely too sure of anything!).

The novel focuses on Freddy, a young woman who keeps finding herself in and out of a relationship with Laura Dean, the smooth, fast talking, charming young titular character of the comic. Freddy doesn’t want to love Laura, but she can’t help herself. Instead of breaking things off and making it final, Freddy finds herself susceptible to Laura’s false promises.

(Spoilers for the graphic novel to follow)

Laura Dean and Freddy

History repeats itself in Laura Dean, and Freddy thinks with her heart more than her head. Even though Laura Dean has serially mistreated her in the past, Freddy falls back into a sort-of relationship with her, much to the disappointment of her friends. If that’s plot A in the graphic novel, plot B involves Doodle, Freddy’s nonbinary friend that becomes embroiled in trouble of their own.

But really, this story isn’t about Laura Dean or Freddy’s obsession with her; it’s about how relationships can turn people into bad friends. Freddy follows Laura Dean through her every whim, showing up to hang out with her supposed girlfriend only to discover Laura’s having a party instead, missing out on what’s happening in her actual friends’ lives to maybe see Laura--all at the expense of her friends like Doodle, friends who are actually there for her. Freddy can’t be there for her real friends while she’s spending all of her time chasing a girl who does not want her, who emotionally manipulates her, and that’s the real lesson of the novel.

Everyone knows someone like this. People get caught up in relationships for better or worse, and just sort of...stop hanging out with their friends. Relationships can be all consuming, especially at first, and especially in high school. Freddy eventually realizes that she’s mistreating her friends, but it takes her a long while to get there and ends up hurting everyone she loves. Still, navigating relationships and who you are while in one is a quintessential part of the teenage experience, and Tamaki has done an excellent job of navigating the complexities of young love while also acknowledging that love sometimes makes you a bad friend.

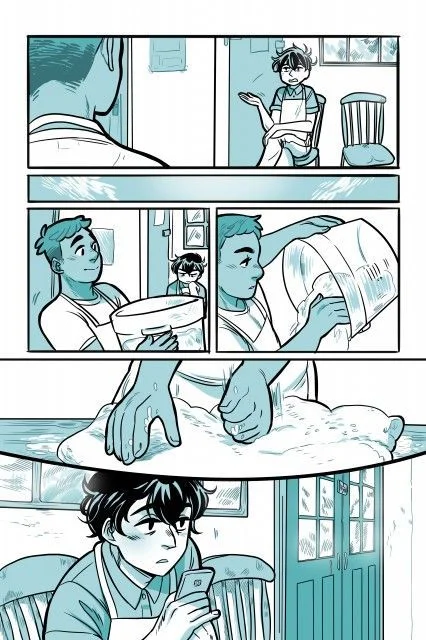

Valero-O’Connell’s work is always lovely, but particularly so in Laura Dean because of her restricted color palette. Valero-O’Connell has been lauded (such as in this review of Laura Dean from Oliver Sava) for her use of color, but Sava notes that Laura Dean has a more muted palette than usual, being mostly monochromatic with pops of pink. While Sava acknowledges that Valero-O’Connell uses those brief bursts of color to her full advantage, I’d argue that she does even more than that. Laura Dean embodies a specific Instagram-like aesthetic that aims to be popular with young people and succeeds in spades. The book is beautiful and has many themes that are popular in design circles right now, like plants, soft colors, abstract imagery. Though the art styles are different and wonderful in their own ways, Laura Dean’s art direction reminds me of Savanna Ganucheau’s work on Bloom, another graphic novel recently released from First Second. Bloom also capitalizes on imagery of the moment: calligraphy/hand lettering, soft colors, strategically used splash pages. It’s not fair to say that this is a house style for First Second, but it’s definitely becoming a trend in comics marketed to young adults in general.

A page from Bloom, which features a similar visual style to Laura Dean.

First Second has also been at the forefront of publishing books about queer romance for young adults, and I’d argue that they’re doing good work at depicting LGBTQ+ relationships as normal, beautiful parts of life. Bloom (by Kevin Panetta and Savanna Ganucheau), On a Sunbeam (by Tillie Walden), and The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang all depict various types of queer relationships and have been popular with awards committees and fans alike--and they were all published by First Second. While it’s not a publisher’s responsibility to market LGBTQ+ books, or to change the landscape of comics with them, First Second is moving in that direction, proving that these types of stories not only sell, but build a fanbase and stir up an interest in comics in general. The next generation of creators will grow up reading these stories.

But let’s get back to Laura Dean. What I appreciate most about this story isn’t the representation of queer communities (which is great), or the artwork (also great), but the reminder that multiple people depend on us daily. Freddy disappoints her friends by constantly ignoring them in favor of hanging out with Laura Dean, and ultimately she misses out on some major life moments. She isn’t there for her friends when they need her because she’s too wrapped up in her own relationship drama--which was repeated several times by this point. No one is an island, and if you are a person who has friends and lives in the world, people depend on you. While self-care and self-advocacy are important, so is being attentive to other people and their needs. We could all use a little bit more empathy when dealing with others, and Laura Dean reminds us that the world keeps moving even when we stop in the same place for too long.

My one tiny gripe with the graphic novel is that at times throughout the story, Freddy hears voices coming from her stuffed animals that she and her friend Doodle make together. Mostly, the animals comment on things that are happening in Freddy’s life or give her advice on what to do next. They may be acting as her inner voice of reason, or represent in a visually interesting way the conversations Freddy has with herself while trying to decide things. However, I wonder if they could also represent some sort of mental illness that remains unaddressed in the story, or if they could represent Freddy’s loosening grip on reality in general. While I wish this aspect of the text would have been explored more, I think the lack of certainty allows for interesting multiple interpretations.

If you enjoy stories about queer communities, beautiful artwork, and narrative twists, make sure to check out Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me by Mariko Tamaki and Rosemary Valero-O’Connell! It’s available from First Second right now!

Doodle helps Freddy after she drinks too much.